Why we should still prosecute Nazis?

- 0 comments

- by KayPage

This week Netflix has dropped its latest debate inducing docuseries, The Devil Next Door and whilst it’s not for the faint-hearted, it is one that everyone should watch.

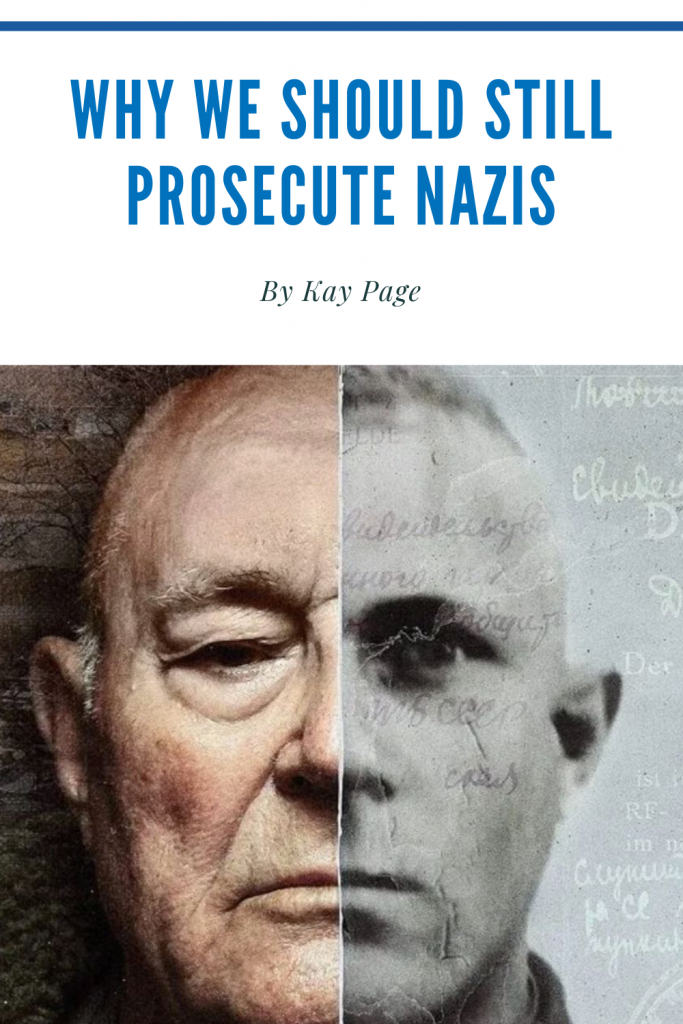

The Devil Next Door focusses on the now-infamous case of John Demjanjuk, a Ukrainian-American immigrant who was once accused of being a feared and renowned Nazi extermination camp guard.

Employed within the Treblinka death camp system, the guard in question was fearfully referred to as Ivan the Terrible by inmates who knew him to be the cruellest and brutalist of them all. Prior to his arrest, John Demjanjuk’s picture was repeatedly identified by survivors who confidently attested that he was the Ivan that they had come to know by that name.

At the time, Demjanjuk was living in the United States and a subsequent investigation eventually discovered a swath of evidence that seemed to prove that was the guard in question.

Despite his defence lawyers continuously raising concerns that he had never even worked for the Nazis, Demjanjuk was convicted in Israel and ultimately sentenced to death. However, despite the powerful testimony and evidence that had been presented at his trial, the verdict was eventually overturned over concerns that his identity could not be definitively proven.

Yet, that was not to be the end of the road for Demjanjuk and he later found himself in a German court, this time accused of being a different guard, at a different camp, Sobibor.

Once again, he was convicted of the crimes, but he died whilst awaiting his appeal. In truth, the evidence seems overwhelmingly supportive of the theory that he was Ivan the Terrible but we will likely never know for certain.

But whilst the series itself focuses solely on the Demjanjuk case, it once again raises decade-old questions about the handling of war crimes and how far we should go in the prosecution of those involved.

Unprecedented

The Holocaust was a unique event in modern history and although it was not the first nor the last genocide, it did change how the world viewed and treated such crimes.

Having never experienced anything quite like it before, it is unsurprising that the global community initially struggled with how to handle those involved and many mistakes were made in the process.

For obvious reasons, it was widely agreed that those in the high command should be prosecuted, but by the end of the Second World War most of the primary Holocaust architects were dead. Others had escaped the country in the chaos that the end of the war had caused.

Furthermore, in the years following 1945 here was little appetite to prosecute such criminals within Germany itself and although many were eventually brought to trial, few actually faced justice. Many of those who were tried were often given ineptly short sentences or outright exonerations.

It wasn’t until the late 80s and early 90s that things really started to change but by this point, it had become increasingly difficult to locate and prosecute those who were known to have been involved.

Is it too late to charge Nazis for their crimes?

Is it too late to charge Nazis for their crimes?

The fall of the Berlin Wall marked a turning point in the history of the Holocaust as it provided authorities with access to never before seen documents. Thanks to the cold war and the wider European tensions over the post-war period, resources had never been widely shared.

The fall of the USSR and therefore the collapse of the wall allowed for investigators – or Nazi hunters – to access documents that provided them with new information. As a result, they were then able to better understand the intricate detail of the concentration camp system and hence build a better picture of what happened. In turn, this meant they could identify culprits and seek to find where they had hidden.

In the years that followed, numerous SS guards were subsequently tried for their crimes, but by this point they were all old men.

For many, this appeared unnecessary or cruel, with some believing that some sort of statute of limitations should probably have been applied.

For us, as the far removed, contemporary observer who are merely viewing these men through the passage of time, it’s easy to see them as softly spoken geriatrics who were probably forced into what they did. Many saw them as having lived their lives with regret

And found it difficult to see them as being the mass murderers that they are.

Perception

All too often we chose to view the Nazis as being monsters, somehow unhuman and we find it hard to equate those evil men with the ordinary seeming men that we now see being brought to justice. To many, these men as frail, softly spoken beings who were once forced to commit atrocities but whom have lived with the burden ever since. But to the millions who died and the few who survived, they will always be a wolf in sheep’s clothing.

There’s a mistaken belief that all of the SS were conscripted, and that these guards were somehow forced into what they did but that is simply not the case.

These men were mostly Nazi fanatics who chose to participate in the murderous actions of the Nazis elite enforcement engines.

Whether they were the accountants, the gas chamber operators or the commandants of the entire camp, they signed up for the SS because of their shared beliefs and they therefore played their part in the entire process.

There’s a painful truth in this debate that most of us struggle to come to terms with – the Holocaust was enabled by ordinary people who chose to look the other way.

That isn’t to say that we should hold an entire people responsible for the acts committed in their name, but those who actively participated have to be brought justice. Justice should apply whether you are 15 or 95 years old.

Important lessons

It’s important that we continue this conversation even now, 70 years after the Nazis first surged to power because whether we want to admit it or not, there are crucial lessons that we must still learn.

It’s easy for us to look at the images, hear the testimony and attest that we will never let it happen again, but whilst anti-Semitism still exists, so too does the risk of another genocide.

It is said that you can destroy a movement but you can never destroy an ideology but that doesn’t mean we cannot challenge it on every occasion and at any opportunity that we get.

When it comes to prosecuting those involved in such atrocities, we have but two simple choices. Either we accept that these were willing participants of the crimes that were committed, and they should therefore be punished as and when they are found. Or we argue that were victims of circumstance and in doing so we affirm that we must do everything to stop those circumstances from ever being repeated.

Prior to the Nazis rise to power, Europe was a powder keg of anti-Semitism and all it took was the right leader, the right rhetoric and the right party for that already vile sentiment to evolve into something altogether more dangerous.

For us, the majority of whom now live in some kind of multicultural society, it can be comforting to see the holocaust as the by-product of one mad man, a set of circumstances that will never be repeated. Yet that does a huge disservice to the testimony of history.

Ultimately the Holocaust was designed by the Nazi high commented, built by the SS senior officers, enacted by those that worked in the camps and fuelled by rampant anti-Semitism.

This docuseries comes just days after a city in Germany declared themselves to be living in a ‘nazinotstand’ – a Nazi emergency. Since 1945, and despite everything that we now know about the Holocaust, Dresden has been a hot bed of anti-Semitic feeling and it continues to see mass support for the far-right. It is the home and birthplace of the anti-Islamic group Pegida and saw the far-right party AfD win over 27% of the vote in September this year.

That means that given the right surge in support, the right set of circumstances and the same sentiments could once again dominate the political dialect. Court testimony gives us a unique opportunity to prosecute those responsible, whilst recording the experiences of those that suffered.

As the perpetrators and survivors move from living history to history, it is vital that we do not allow the lessons to do the same.

In this is perhaps the single most important point, that antisemitism still exists and it did not die with Adolf Hitler.